THE

BREAK

ROOM

Bill Wheeler

If you work in the design business in Southern California long enough you will eventually work on a project that has something to do with the entertainment industry. That project might be a tenant improvement inside an amusement park, or better yet, a ride inside that park. You may work on the expansion of a support building for one of many studios or you may do engineering for a one-of-a-kind set inside a sound stage for a blockbuster movie. For the sports fans among us, you may have worked on a project at the Rose Bowl, the Coliseum, Staples Center, or any one of dozens of other sports venues from here to San Diego. We’ve all had or will have that experience if we do this work long enough in Southern California.

If you work in the design business in Southern California long enough you will eventually work on a project that has something to do with the entertainment industry. That project might be a tenant improvement inside an amusement park, or better yet, a ride inside that park. You may work on the expansion of a support building for one of many studios or you may do engineering for a one-of-a-kind set inside a sound stage for a blockbuster movie. For the sports fans among us, you may have worked on a project at the Rose Bowl, the Coliseum, Staples Center, or any one of dozens of other sports venues from here to San Diego. We’ve all had or will have that experience if we do this work long enough in Southern California.

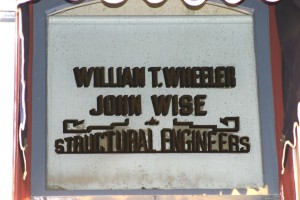

There are, however, only a few who have had their names literally etched onto the most iconic of Southern California landmarks. Next time you’re at Disneyland, after passing under the Disneyland Railroad, turn right and head over to the Disneyland Bank. There, on a second floor window, you will see the names of William T. Wheeler and John Wise and below you will see Structural Engineers.

There are, however, only a few who have had their names literally etched onto the most iconic of Southern California landmarks. Next time you’re at Disneyland, after passing under the Disneyland Railroad, turn right and head over to the Disneyland Bank. There, on a second floor window, you will see the names of William T. Wheeler and John Wise and below you will see Structural Engineers.

Bill Wheeler was a key member of the design team that helped create Disneyland. John Wise was Bill’s employee who later became Disney’s chief engineer. The window above Main Street has been there for decades, but after it was installed Bill led design teams that were instrumental to the Disneyland we see today, and also to Disney World and Epcot Center in Florida, a series of parks throughout the world and thousands of other projects that form the fabric of Southern California, many of which we see every day as we drive through California.

Bill Wheeler was born at the beginning of the twentieth century, before there was an interstate highway system and before many of the most famous engineering and construction projects of the century were built. Without Bill and people like him, those projects wouldn’t have been completed.

Bill Wheeler was born at the beginning of the twentieth century, before there was an interstate highway system and before many of the most famous engineering and construction projects of the century were built. Without Bill and people like him, those projects wouldn’t have been completed.

Most people begin their first trip to Disneyland in the family car and on the way they talk about which rides they’ll go on when they arrive at the park. Bill’s journey to Disneyland started in Chaney, Oklahoma, his birthplace, where his family farmed the land. In 1915 Bill and family took their first E-ticket ride. His family packed up and moved to Baca County, Colorado – by covered wagon. By 1922 his parents had decided that their sons needed better opportunities for education, so they traded in the covered wagon for a Ford Model T and headed to California. They stopped in the San Joaquin Valley where Bill’s father managed farms and his mother taught school. Bill took advantage of the opportunities. He graduated from Delano High School in 1929 and was accepted at California Institute of Technology, Cal Tech to most of us, where he studied civil engineering along side other super smart men and women who were figuring out how the world works.

Bill worked his entire life and each job was more interesting than the one before. To help pay for school and expenses Bill worked in the farm fields of the San Joaquin Valley during college breaks and on campus when school was in session. During one Christmas break Bill spent his time in the San Joaquin orchards keeping smudge pots fueled and burning to warm the citrus crops. At school he worked at the Cal Tech faculty club, the then newly opened Anthaneum, where he served meals to faculty, including, rumor has it, to Albert Einstein. No word on what Mr. Einstein ordered for lunch.

Bill worked his entire life and each job was more interesting than the one before. To help pay for school and expenses Bill worked in the farm fields of the San Joaquin Valley during college breaks and on campus when school was in session. During one Christmas break Bill spent his time in the San Joaquin orchards keeping smudge pots fueled and burning to warm the citrus crops. At school he worked at the Cal Tech faculty club, the then newly opened Anthaneum, where he served meals to faculty, including, rumor has it, to Albert Einstein. No word on what Mr. Einstein ordered for lunch.

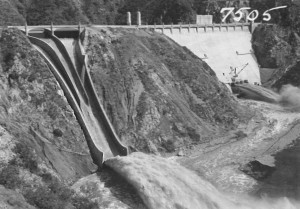

After graduation from Cal Tech with a degree in civil engineering Bill took jobs building the Southern California infrastructure that today we take for granted. He worked on Morris Dam for Pasadena Water and Power, Los Angeles’ Union Station for the consortium of the Santa Fe Railroad, Southern Pacific Railroad and Union Pacific Railroad and the Golden Gate Bridge for the Ceco Corporation, a steel fabrication company that produced reinforcing steel for the bridge. Bill worked for the Los Angeles District of the Corp of Engineers on the Los Angeles River, then moved to Sacramento in 1938 to work for the Office of the State Architect until the beginning of the war. By then married with children, he took a job with the United States Army’s Quartermaster Corp in Ogden, Utah, which was absorbed by the Army Corp of Engineers during World War II. The Corps of Engineers kept Bill busy during the War engineering state-side military infrastructure that was critical to an Allied victory. The Corp moved Bill back to California in 1943 and he finished work for the Corp in 1945.

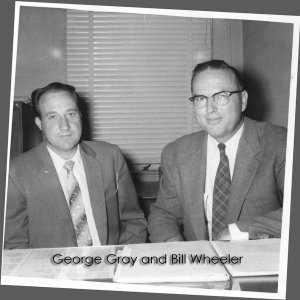

After the Corp, Bill briefly worked for a private company and then, as he said, hung his own shingle on March 1, 1946. (Yes, this year Wheeler & Gray turned the stately age of 70.) By that time, Bill had worked on Union Station, the Golden Gate Bridge, designed major military infrastructure during World War II, married, started a family and worked on more high profile projects than most of us will work on in our entire careers. The journey began riding in a covered wagon and coming to California in a Model T, which is a good start to any story, but then you have to finish big.

After the Corp, Bill briefly worked for a private company and then, as he said, hung his own shingle on March 1, 1946. (Yes, this year Wheeler & Gray turned the stately age of 70.) By that time, Bill had worked on Union Station, the Golden Gate Bridge, designed major military infrastructure during World War II, married, started a family and worked on more high profile projects than most of us will work on in our entire careers. The journey began riding in a covered wagon and coming to California in a Model T, which is a good start to any story, but then you have to finish big.

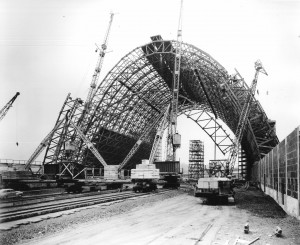

In 1952, Jack Rorex was in charge of engineering and construction at Disney Studios. Also at Disney was Al Palo, who worked with Bill on the Union Station project. Jack was looking for a licensed engineer to design a large stage at the studio and Al recommended Bill for the work. The stage was for “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” winner of two Academy Awards and the second highest grossing movie of the year. There is no Oscar for structural engineering, but maybe there should be. In 1954, after a couple years of work at the studio, Jack took Bill to meet two people who were working on a special project that Walt Disney was overseeing himself. Those two people were Dick Irvine and Joe Fowler. Irvine had recently been the art director at 20th Century and Fowler was a retired Navy admiral. They were heading the Disneyland design group, WED Enterprises, now known as Walt Disney Imagineering, the home of the Imagineers.

After a decades long journey that started on a farm in Oklahoma, that passed through the orchards of California’s Central Valley and included intersecting and joining paths with men with household names like Albert Einstein and Walt Disney, Bill was back working in the farm fields – of Anaheim. After what would today be considered an impossibly short time, Disneyland opened in 1955. But The Magic Kingdom wasn’t complete. Many of the best known attractions of today were completed after the initial opening. Bill and his company continued to work on the completion of the park and its expansion for many years. The Matterhorn, the Monorail, and dozens of other attractions came to life. At the same time, Bill was cultivating relationships with other clients from so many different facets of Southern California life that it’s impossible to name all of them. Bill’s clients included the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, Coca Cola Bottling, The Salvation Army, every branch of the U.S. Military, the state of California and so many cities and counties that it’s easier to name the ones for whom Wheeler & Gray did not work.

After a decades long journey that started on a farm in Oklahoma, that passed through the orchards of California’s Central Valley and included intersecting and joining paths with men with household names like Albert Einstein and Walt Disney, Bill was back working in the farm fields – of Anaheim. After what would today be considered an impossibly short time, Disneyland opened in 1955. But The Magic Kingdom wasn’t complete. Many of the best known attractions of today were completed after the initial opening. Bill and his company continued to work on the completion of the park and its expansion for many years. The Matterhorn, the Monorail, and dozens of other attractions came to life. At the same time, Bill was cultivating relationships with other clients from so many different facets of Southern California life that it’s impossible to name all of them. Bill’s clients included the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, Coca Cola Bottling, The Salvation Army, every branch of the U.S. Military, the state of California and so many cities and counties that it’s easier to name the ones for whom Wheeler & Gray did not work.

For all his salesmanship skills, Bill wasn’t a salesman. He was an engineer’s engineer. He served as President of the Structural Engineers Association of Southern California (SEAOSC) and started its seismology committee. He led SEAOSC’s effort on the “Blue Book,” the first edition of what would become a uniform seismic code. Much of what Bill’s committee developed was adopted into building codes. The code today may be a distant relative of SEAOSC’s first Blue Book, but the Blue Book is what led to uniformity.

Born into a farming life, Bill pursued an education and graduated from Cal Tech with honors, met Albert Einstein and worked for Walt Disney, worked on Los Angeles’ Union Station, the Golden Gate Bridge, the Rose Bowl, court houses, and schools, worked for industry and government, helped lay the ground work (pun intended) for modern seismic codes, and of course, was the structural engineer for Disneyland. His work continues even though Bill is no longer with us. So, the next time you’re at Disneyland, stop by the bank, check out the window, then head up Main Street for a root beer float and raise a glass to Bill.